The letters here, the ones you are currently reading, don’t exist in any palpable form, they’re the result, as you no doubt know, of electricity exciting a liquid crystal. They’re virtual letters and only come into touch with reality when ink is spat through those tiny jets. There’s no feeling to them, the breath of humanity passes them by, as indeed does the sweat of the compositor swearing shittyfuckbollocks as he drops a case of type.

Letters for most printed things used to be made of lead, well yes, you’re right, they were made of wood before they were made of lead,

but they were lead for a long time and they had weight, they had substance. As anyone who has brandished a bossing stick:

braying flashing over a bay window will know: lead’s a Nice Thing to Hold.

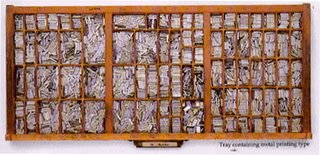

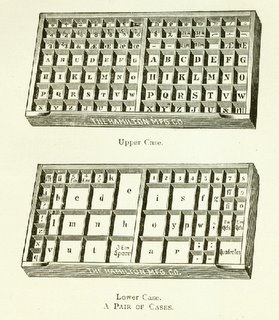

These lead letters were kept in type cases, which were wooden trays divided up into small compartments – now mainly seen on kitchen walls, usually containing things that should rightly be in the bin.

Of the two cases that contained the font of a particular typeface, the upper case had all the capitals, the lower case had all the small letters. The letters were all in individual compartments, in the upper case the compartments were mainly the same size, in the lower case the sizes varied with the popularity of the letter, the e compartment was the biggest.

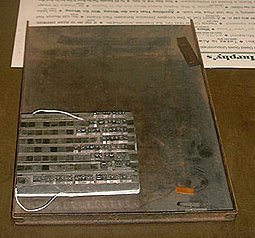

Individual letters would be plucked out of the case. There was a nick on one face and you had to feel for this with your thumb nail so you could set all the letters the right way up. Your left hand [or right if you were left handed] held the stick, with your left thumb holding the assembled type in place.

The stick was set to a line length and as the words got close to the end of the line you would fill the gap with blank em’s or en’s or tiny slivers of brass to make everything tight. If the copy was justified you would have to have to insert spaces between each word.

You could set two or three lines of type in the stick then you had to transfer them to the galley tray. It was a good trick to get the type out in one piece, and a nightmare if you didn’t.

When the lines were set and the section was complete you had to wind a bit of string round all the type to stop it falling All Over the Place. The knot to secure this was a tricky number, sort of slipped and tucked under the winding at a corner.

Enough for now, go away and practice the above until it becomes second nature and your hand reaches automatically to the correct compartment, faultlessly plucking letters out at a mind-bending speed.

The Holmfirth Typographical Society would like to thank Matthew Kirschenbaum, Assistant Professor of English and Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, University of Maryland for some of the pictures in this article. To see more images and a good description of the process just click here and you shall be sped across the internet to Amerikey.

1 comment:

Does anyone still do this anywhere, or is it completely gone, except as a curiosity? Strange to think that so much skill was involved and that there must be hardly anyone left who knows how to do it.

Post a Comment